Since working as a clinical psychologist at the Third Circuit Court Family Division (Juvenile) Clinic for Child Study the past 12 years, I have noticed a trend: the entry of an increasing number clients who identify as of LGBTQ/GNC (lesbian, gay, biattractional, transgender, questioning, and gender nonconforming).

It did not occur to me that this was a nationwide observation until I consulted the literature. Having already known that Black youth were disproportionately represented in the juvenile system long before I began working at the Clinic, and seeing the increase over time, I was surprised to see that LGBTQ/GNC youth were also overrepresented in the same system. Having known the various factors associated with Black youth incarceration, I had yet to find out why there were so many LGBTQ/GNC youth entering the juvenile justice system.

Once I found out from researchers what the risk factors were, I had spurts of “aha” moments. From having been familiar with other research on LGBTQ/GNC youth, including homeless youth, due to my exposure to the Ruth Ellis Center, Ali Forney Center, and other agencies, it became more clear why these youth were becoming more visible in juvenile justice settings.

Here I was, in the middle of a juvenile court clinical workplace for so many years, and no one had pondered why this was happening, including myself.

As I read the literature, my head nodded from article to article. I knew that the identified risk factors were real. I’ve heard the stories from my LGBTQ/GNC clients and from youth I have encountered since 1999 when I co-founded the Ruth Ellis Center, which is a social service agency serving homeless, displaced, and runaway LGBTQ/GNC youth. The Center primary racial demographic is African American.

Putting two and two together, I said to myself that if being Black is a risk factor, and being LGBTQ/GNC is a risk factor, what if a child/teen was both Black and LGBTQ/GNC? This intersectional question troubled me to some degree. Two strikes against Black LGBTQ/GNC children.

However, I became more aware that these were not the only risk factors. Being Black and being LGBTQ/GNC by itself is only part of the story. There had to be certain circumstances that lead many of these youth to interface with the juvenile system, many of which are systemic and many in which are familial. Most notably and most basic is family rejection.

Instinctively, those of us who care about children are aware of the impact of family rejection in general. It makes us cringe when we think about a parent kicking their child out of the house or abusing or neglecting their child. However, to reject one’s own child for being LGBTQ/GNC may seem to be an acceptable behavior for too many families, and it occurs more frequently than we think. Once a child is turned into the streets, it begins a change of events that place them at-risk for legal involvement, among other dilemmas.

Family rejection is one area. School is another. By law, children must attend school. Yet, constant bullying, abuse, and harassment at school can potentially lead to premature school drop-out rates and truancy which can often find youngsters in the streets in a “homeless” state until they are picked up by the police. In addition, LGBTQ/GNC students who have had to endure bullying on a daily basis are apt to defend themselves as a healthy coping practice. What can happen is the risk of being the one suspended or expelled for doing so. In some instances, the bullied student can end up in the juvenile system just for trying to protect one’s self. If they don’t go into the juvenile system, these youth may end up going into the foster care system where, again, LGBTQ/GNC of color are overrepresented.

Having knowledge and insights on some of the avenues that lead this population into a system of punishment can help mental health providers understand more fully the dilemmas under which Black LGBTQ/GNC youth undergo, and appreciate the stamina, courage, and resiliencies they have. Black youth tend to stereotypically be criminalized and this is a known fact by many. But when it comes to LGBTQ/GNC, their tendency to be criminalized is not common knowledge. My colleagues at the Clinic were unaware of this fact and how such youth’s court involvement may be a result of their victimization rather than being a perpetrator.

My hope is that mental health providers, families, and juvenile justice administrators read my article. It only scratches the surface of the multiple, complex, systematic, cultural, and institutionalized factors effecting Black LGBTQ/GNC youth who end up in the juvenile justice system. In it, I make practical recommendations from policy changes to family therapy and reunification.

It is my intention to influence social justice into the direction of providing safety and positive health outcomes through making this unique and marginalized population of youth more visible and understood.

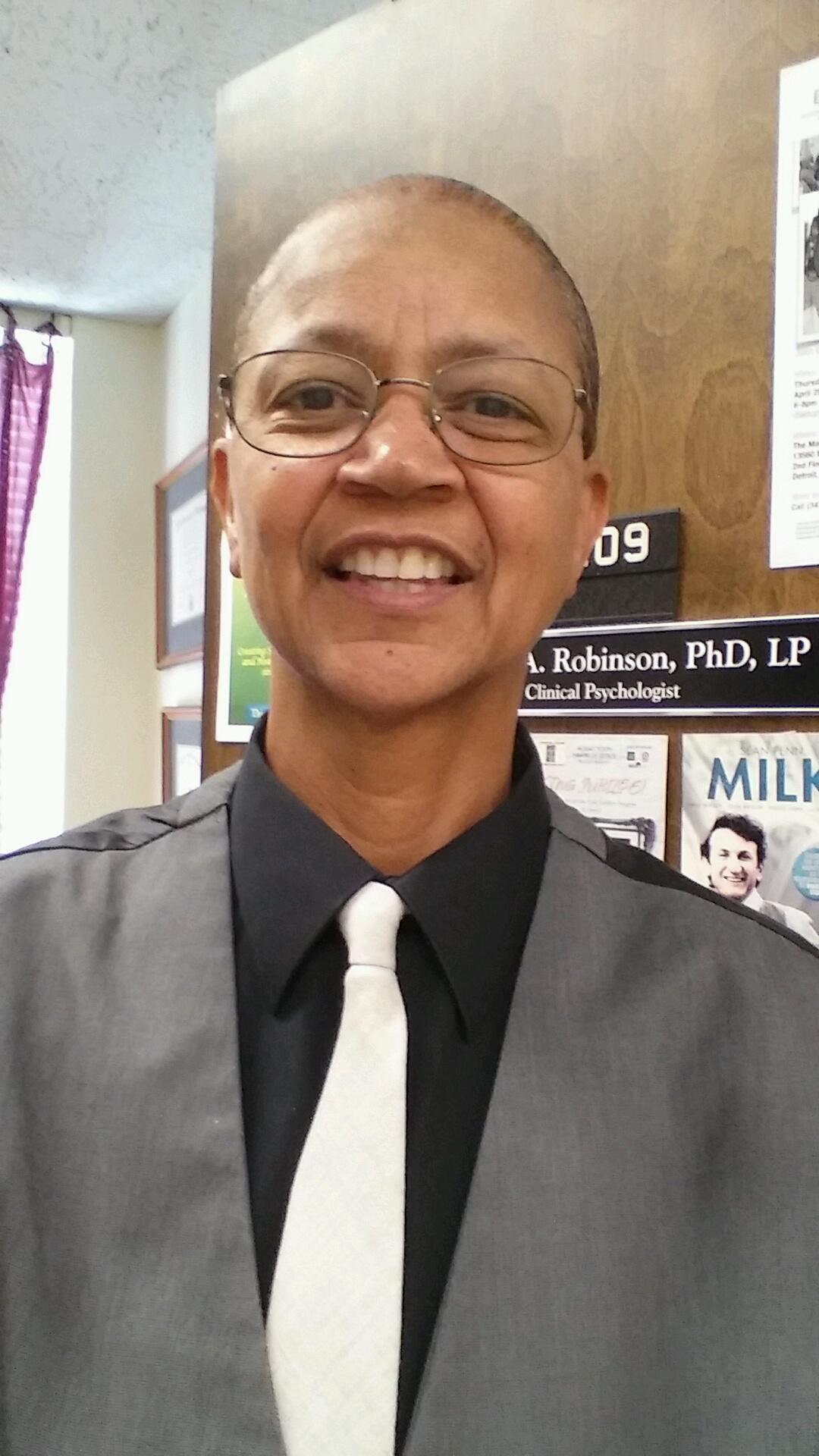

Amorie Robinson, PhD, LP is a contributing author to Black LGBT Health in the United States: The Intersection of Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation that was published in December 2016. Dr. Robinson works full time in Detroit at the Wayne County Third Circuit Court Family Division Clinic for Child Study conducting therapy with adjudicated youth and their families. As a psychotherapist at Counseling Associates, Lewis & Mikkola Psychological Services, and Northland Clinic (presently), she has spent 24 years working with adults, adolescents, and children.

Amorie Robinson, PhD, LP is a contributing author to Black LGBT Health in the United States: The Intersection of Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation that was published in December 2016. Dr. Robinson works full time in Detroit at the Wayne County Third Circuit Court Family Division Clinic for Child Study conducting therapy with adjudicated youth and their families. As a psychotherapist at Counseling Associates, Lewis & Mikkola Psychological Services, and Northland Clinic (presently), she has spent 24 years working with adults, adolescents, and children.